- Home

- Gary Newman

The Ruffian on the Stair Page 9

The Ruffian on the Stair Read online

Page 9

After a few minutes, I dragged myself up and went into the kitchen, where I uncorked a bottle of Merlot and poured myself a glass before supping off a slab of cheese between two hunks of wholemeal bread. As I munched and grew mellower with the soft wine, I mulled over the Rawbeck business, and in particular the new aspect of it introduced so theatrically by Liam Brogan the previous night.

My grandfather, then, had done his runner from the murder room over the lowlife pub on that November night in 1899, then, on packing his things in his digs before decamping to Paris, had noticed that his initialled, family-heirloom razor was gone from the washstand. On the same night, Philip Forbuoys, who played the flute at the magic mushroom session at which my grandfather was also present in the house on Camden Hill only hours before, apparently fills his pockets with stones, jumps into the Thames and drowns. According to the contemporary Times report, Forbuoys ‘apparently’ bought a second-hand razor earlier that day, since his own was found afterwards in his lodgings.

Now, on the eve of Good Friday more than a century later, Liam Brogan produces my grandfather’s long-missing heirloom razor, looted, as far as I knew, from his effects by a Jersey neighbour in the troubled invasion summer of 1940. Working on the assumption that Grandfather didn’t use his own razor to cut Julian Rawbeck’s throat and absentmindedly leave it behind, the crucial question was: where had the razor been between the time it went missing from Grandfather’s London digs on 10th November 1899, and the time, sometime this year, when Liam Brogan presumably bought it from the old rogue who’d been my grandfather’s thieving parishioner? Did Grandfather get it back from someone in the meantime, and in which case, from whom? And, most crucially of all, was it the razor that had cut Julian Rawbeck’s throat?

I recharged my glass with Merlot and went back into the sitting room, where I got the fire going again with old fish-and-chip paper and wood shavings. I rested a half-log on the blaze, retired to the cane armchair, and pursued my train of thought in comfort. My ear felt cold leather, and I reached up to my bomber jacket, which I’d draped over the back of the chair. Instinctively, my hand went for my grandfather’s notebook in the inside pocket. It would all be in there, I thought: the answer to the riddle would be in there somewhere . . .

I riffled through the tired pages of the cheap little book, my attention lighting on the section with the disjointed phrases: Rivers we now knew, Reuben’s Court we thought we’d dealt with for the time being, and Smoking Altars looked literary, but Home in the East and Soundings A? Figuring as they did in this record of what must have been the most shattering events in my grandfather’s life, they must have been of crucial importance to an understanding of the Rawbeck affair, but what did they mean? I glanced up at the mantelpiece and searched my grandfather’s eyes in the photograph, but he was saying nothing . . .

I sighed, and was about to lay the notebook aside: might as well throw dice for an answer . . . But yes, there was a modern equivalent of dice: the Internet. I got up and found Grandfather’s 1871 street plan, and took it upstairs with his battered notebook, and started up the computer. I got into the search engine, and typed Home in the East into the box, then clicked on Search.

A long list of Indian restaurants and takeaways appeared: in Luton, Leicester, Coventry and Peterborough, with one in London. I clicked on the London one: it was in Iceland Road, in Hackney. In my grandfather’s young days, Hackney was for the most part a humdrum, lower middle-class residential district, but with shady patches and rough edges to it. I reached over my desk for the modern London street plan, and found the grid with Iceland Road in it. Comparing this with the equivalent on the 1871 map, my suspicions were confirmed: virtually the whole district had been ripped out to make way for the northern approach road to the Blackwall Tunnel.

The pub with the horror room above it must long since have been swept away, and the stairhead window with the beguiling colours shattered into a million ruby and blue fragments by the blind snout of the bulldozer. But, hang on, Iceland Road went down at right angles to the Lee Navigation Canal. I recalled the detail in Grandfather’s account of his flight from the murder room in that raw, pre-dawn in the November of 1899: water on my left. And Soundings A came immediately after Rivers in the notebook. Was there any street or other townscape feature with Soundings in its name?

I looked up the index of the modern London street plan: there was a Sounds Lodge, but that was in Swanley. Turning to the 1871 map, I trawled my magnifying glass from the desk drawer and ran it carefully over the upper left-hand corner of the dirty, linen-backed paper. Iceland Road was there, branching off towards the canal at right angles towards the bulge of the easterly sweep of the Old Ford Road, as it must have been before the modern approach road had been built. And, yes! – there, bisecting the semicircle drawn by the sweep of the Old Ford Road, was Soundings Alley – hence the A.

But what made me spring back in my seat with excitement was the little black box on the old map, just a little up the curve of the Old Ford Road, with the words Home in the East. This was more like it! I returned to the computer keyboard, typed in Hackney Home in the East, clicked on Search, and directly the earnest face of a Victorian philanthropist flashed on to the screen. I took in the introductory text at the bottom of the photo:

Nonconformist Julius Benn, late of Manchester, in 1851 moved with his wife Ann to London, to take up work in the London City Mission in Stepney, the couple eventually moving farther north to Hackney, where they opened the Home in the East, a refuge for homeless boys in the East End.

I scrolled down and read the rest, but there was nothing there that I could tie in with my grandfather’s astonishing adventure. I supposed it would all be gone, now. So: Rivers, a boys’ home in Hackney, an alley through the Old Ford Road, and a canal that bordered the marshes. Link them all up, and Bob’s your uncle!

I turned to the old street map again, and gave the spot that featured the boys’ home and Soundings Alley a good once-over with the magnifying glass, but no sign of any pencilled markings. But, although I still couldn’t link them all up logically yet, I’d at least cracked the rest of the enigmatic references in the notebook – with the nagging exception of Smoking Altars, of course. I immediately rang Leah at the university to tell her about my findings.

‘Interesting,’ was her initial response. ‘Now all you’ve got to do is get some actual meaning out of the stuff.’

Something occurred to me.

‘Yes,’ I replied, ‘it’s possible, too, that Grandfather only marked the places on the map that he’d already checked out. The complete list of places still to be checked out by him in his search for the murder room could’ve been on one of the pages of the notebook that have been torn out. And that raises the question of who tore out the pages – but I’m jumping the gun.’

‘Yes,’ Leah said. ‘I think you’ve done well – made real progress – and as for the torn-out pages, didn’t this old guy in Jersey who’s supposed to have pinched your grandad’s things have kids?’

‘Yes, a son, and now a grandson – the little lad who pointed me out to Reet and Frank and Pat Hague a couple of years ago when we were all on holiday on the island.’

‘The kid who asked his dad if you were the man in the shed?’

‘Right, but what are you getting at?’

‘Well, kids like nothing better than scribbling in books and tearing the pages out of them, so I don’t think there’s any need your going on flights of fantasy about who might have had dark motives for tearing out evidence.’

‘Typical common sense,’ I remarked. ‘Leah, what would I do without you?’

‘I shudder to think.’

I laughed, but then something else came to mind.

‘The little boy in Jersey might’ve been playing with my grandfather’s things in his grandad’s shed,’ I mused aloud, ‘but why should he have asked if I had been in it? To my knowledge, I’ve never been inside a shed in Jersey in my life.’

‘Search me, I’

m no child psychologist, but this is a real lead, Seb: will you be going up to Hackney?’

‘I’ll ring the Local Studies people there after the holidays, and if there’s anything left of the district as it was in 1899, I’ll go and suss it out. I’m afraid on first blush, though, it looks as if the approach road to the Blackwall Tunnel is all there is to be seen there now. What are you doing this evening?’

‘I’ve some people from the department coming round for a meal – how about my popping over lateish tomorrow morning?’

‘Fine – we can talk it all over.’

I rang off, then went back upstairs, shut down the computer and started to pace the workroom, my brain racing with fresh speculation, until weariness took over. Before heading downstairs again, I glanced out of the window at the marshscape. It was dusk now, with a riding moon visible in the gaps between the clouds: a tame contrast to the ‘sky roaring with stars’ as described by my grandfather in his notebook account of the mushroom session on Camden Hill way back in 1899.

I was turning away, when something caught my eye far off on the headland. It was a straight, motionless human figure, but in the dimity light I couldn’t make out which way it was looking: straight at me, or out into the distance where marsh and sea joined. I peered at the figure for some time, but it remained steadfastly motionless, then I finally pulled myself away. Some citizen exercising his dog, I reasoned as I went down the stairs, or a late-night fisherman probing for lugworms in the mud. All the same, it gave you the creeps seeing him standing there like a statue. Just then I shuddered, as if someone had walked over my grave . . .

Chapter Nine

Next morning, Saturday, Leah arrived around eleven-thirty, having cleared her desk at the university, and we talked over my Internet finds of the previous day. The upshot was, we decided to drive up to Hackney to do a bit of field research; and in particular, round the subject of the Home in the East.

The weather being a bit on the lowering side, we had a fairly clear run to London, accessing the particular district of Hackney we were interested in by the A11. Iceland Road – what there was of it – ran down from a cluster of industrial buildings just east of the A102 to the Lee River. The whole area was cut through by the A11 and the A102 motorway, which converged on the Blackwall Tunnel, and amid the trading-estate bleakness, there was no trace to be seen of the Hackney of 1899. I parked the car on a space near the Northern Outfall Sewer, and we surveyed the twenty-first-century desolation.

‘It’s all been swept away,’ Leah remarked. ‘Nothing of the original streets – not even the directions.’

‘Mmm . . . Iceland Road’s about the only street in Grandfather’s 1871 map that’s still in the same place.’

We retreated, somewhat deflated, to the nearest seriously populated area round the bus garage in nearby Bow, and sought out a safe-looking parking space near a decent pub, where we ordered lagers and tikka baked spuds, and made our numbers with the older regulars.

‘All gone in the bombing, mate,’ or variants thereof was all we got in response to our enquiries about Soundings Alley, Victorian pubs with colourful windows, Homes in the East or legendary murders. As for the rest, the usual inner city bleakscape of isolated stumps of scruffy pre-war brick terrace, unplanned scatters of council housing, plonked, willy-nilly, over the former street-grid, Brutalist concrete municipal utilities, roaring motorways and unexplained wastes, and all done over by the graffiti –maxims of the gawky – of the local redundant youth. It seemed you had to look farther north and west for the better-preserved pre-war streets, now being furiously gentrified – the ones ‘worth burgling’, as one pub wiseacre had put it. Of course, it being the Easter weekend, the usual information sources were closed, so I’d have to contact them on Tuesday. We tried in another couple of pubs, but with the same result: my grandfather’s East Hackney was gone.

At last I drove my uncomplaining companion – she said she’d enjoyed the crack in the East End pubs – home to Essex and the university, where she’d be entertaining some colleagues later on, then started through the little township towards my lighthouse. But first, if he was at home in the flat above his shop, I’d some questions to put to Frank Hague about potential fellow antique dealers in the vicinity, particularly puckish Irish ones who shone torches through shed windows after midnight . . . This would be an especially convenient time to call on him, since Pat was always at the boathouse at weekends.

Driving slowly past Frank’s shop, I caught the eye of the man himself in the window. He grinned at me, and made an elbow-bending gesture – one for the road? – so I pulled up in a space farther up and went back to the shop. He unlocked the door, with its Closed sign sported, and invited me cheerfully into the wax-smelling front shop, with its mellow-coloured oak, walnut and mahogany wares. I went in, and Frank closed the door again, and clicked the little brass inside-hasp shut behind us.

‘Midnight oil . . .’ I remarked chirpily, as Frank led me into his backroom-cum-workshop with its couple of done-in, 1830 leather armchairs in front of the original fire grate with the electric fire in it. I sank into a flaking armchair, while my host rustled up drinks from the bric-a-brac that filled the room.

‘You know how it is, Seb,’ he remarked, handing me a glass of malt whisky before flinging himself, glass in hand, into the opposite chair. ‘We poor tradesmen have to work all the hours God sends.’

‘I should be so poor,’ I murmured, after I’d taken my first smoothly smoky sip, ‘drinking malt like this . . .’

A snuffle of laughter.

‘My one vice, boss!’ Frank exclaimed.

‘And the rest . . .’

‘How’s the scribbling lark going, then?’ my old school chum asked.

‘My last book’s now in the Amazon six-figure rating – thank God for gardening magazines . . . Something I’d been meaning to ask you, Frank – trade matter . . .’

The hazel eyes behind the narrow-framed specs turned foxy again.

‘I’m always ready to talk business, Seb – fire away.’

I fished in my pockets, and found Liam Brogan’s business card, which I passed to Frank.

‘Has he come into your ken, Frank?’

‘Yes, he was here on Thursday afternoon, actually. Do you know him?’

My host handed me back the card.

‘I know him now,’ I said. ‘He came round to the lighthouse on the, er . . . knock, late on Thursday night.’

‘Right – busy character – he told me someone had recommended me to him at the salerooms in Walberswick the other week.’

‘As the doyen of the local dealers?’

The snuffling laugh again. ‘Naturally – last court of appeal, and all that.’

‘I hope I’m not breaking any professional taboo or anything, but what’s he after round here?’

‘He thinks someone local may be sitting on a lost Impressionist masterpiece – a major minor Impressionist one, if you see what I mean.’

I nodded and took another sip of the fine whisky.

‘Did he specify which masterpiece?’

‘Not really,’ Frank replied. ‘I got the impression he was following up some lead from Jersey. He struck me as a slippery type – just picking my brains, but I charge for that.’

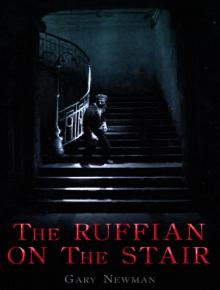

‘Quite right, too! For your information, though, I’m pretty sure the painting’s The Ruffian on the Stair, by Julian Rawbeck, circa 1899.’

Frank’s eyes glittered, and he drew his head back sharply.

‘When I saw the Jersey address on the guy’s card,’ he went on, ‘I thought straightaway of you – the farmhouse over there, and all. You haven’t got the painting, have you, Seb?’

The last remark was in fun, of course, but I kept a straight face.

‘If I had, how much would it be worth to me?’

‘Well, it’s a legendary – almost mythical – painting, what with Rawbeck’s disappearance at the turn of the last century, and so on – no one’s actually seen it, as far as is known. And wit

h a provenance like that – and Rawbeck was a good painter, quite apart from anything else – shall we start the bidding at, say, half a million?’

I reflected that, for that kind of money, quite a lot of people would be prepared to do a lot more than shine a torch through the back window of your shed at dead of night.

‘That was all Brogan wanted?’ I went on. ‘Information on the painting?’

‘Mmm . . . yes, and to say that he’d be offering a few articles himself at the sale at Walberswick on Friday, and hoped he’d see me there.’

‘I wonder if Brogan’ll be offering articles on a Rawbeck theme?’ I probed. ‘Smoke out potential local Rawbeck collectors by using a sprat to catch a mackerel . . .’

‘Just what I was thinking, Seb – he’s flying a kite down here in the sticks.’

‘Will you be going to the auction, Frank?’

‘Oh, I don’t know – I’ve a lot on at the moment.’

‘I can take a hint!’ I said, getting rather creakily to my feet – it had been a long day – and putting my empty glass down on Frank’s desk. ‘As smooth a drop of malt as ever I tasted.’

‘Any time, Seb.’

‘Well, thanks again for the drink – I’ll leave you poor tradesmen to your toil.’

Frank escorted me to the shop door, and saw me out, then, just as I was stepping on to the pavement:

‘Lock up carefully before you turn in tonight, Seb, and watch out . . .’

‘Oh?’ I said, half turning my head. ‘What for?’

‘The Ruffian on the Stair!’

I laughed back and said my final goodnight before the key rattled in the lock of the shop door, to be followed soon after by the whirring of the descending security shutters. You never quite knew where you were with Frank. And, yes, I’d definitely be looking in at Friday’s auction sale in Walberswick.

The Ruffian on the Stair

The Ruffian on the Stair