- Home

- Gary Newman

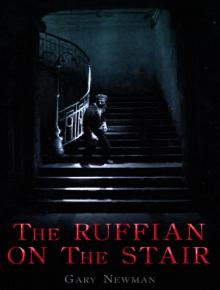

The Ruffian on the Stair

The Ruffian on the Stair Read online

The Ruffian on the Stair

THE RUFFIAN ON THE STAIR

Gary Newman

Constable • London

COPYRIGHT

First published in the UK by Constable, an imprint of Constable & Robinson, 2008

ISBN: 9781780336398

All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Copyright © Gary Newman, 2008

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Constable

Little, Brown Book Group

Carmelite House

50 Victoria Embankment

London, EC4Y 0DZ

www.littlebrown.co.uk

www.hachette.co.uk

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter One

Going over this in my little corner of the early 2000s, I still haven’t come to terms with what’s happened. Never shall, completely, I suppose, but let’s start with the notebook. God! I was actually pleased when, all innocently, it arrived with the rest of my legendary grandfather’s effects in the banal Jiffy bag from the lawyer in Jersey. On an April Saturday it was, by the normal postman’s van, on his daily visit to my lighthouse at the foot of the headland in the Essex mudflat where I live – more or less – as a freelance writer. Gardening articles and occasional film biographies are my subjects, by the way – one or two of you might even have read some of my stuff – but back to the notebook. As to how it turned up at all with the other things, the lawyer explained in his covering letter:

Dear Mr Rolvenden, :

I’m enclosing some possessions of your late grandfather and namesake, Sebastian Rolvenden DD. As you no doubt know, he was vicar of St Marc’s here from October 1919 till June 1940, when he and his lady were rounded up by the Germans with other former mainland residents and sent into internment in Germany. The objects enclosed were left on the doorstep of my office in a supermarket carrier bag, and I don’t envisage that the donor will be traced, nor do I have any knowledge of the contents of the written matter. I understand you still own a property on the island, and will be happy to see you on your next visit to Jersey.

Yours sincerely,

H. E. Le Touzel

As soon as the Jiffy bag had arrived and I’d opened it, Leah – my significant other – and I had started to run through the contents, and I’d lit immediately on the notebook. It was scuffed, crumbling and ancient, the Victorian forerunner of the marble-backed jobs you could buy in post offices for fifty pence or so up till about ten years ago. Many of the pages had clearly been torn out. I’d turned back the cover and there, on the first, untitled page, was my grandfather’s hasty, angular handwriting in faded black ink. But the contents were something different, as we soon learnt when I began to read them out to my companion who sat with one neat, firm leg under her in the window seat and rummaged through the Jiffy bag.

‘Julian Rawbeck is a great artist,’ I read out my grandfather’s words, ‘but he paints in blood. What fate drew me to the Arches on that cursed evening? The sign – yes, the sign on Gatti’s music hall – “Miss Carrie Bugle – Colour in the Shadows – Artiste of the Adagio”. Then the fume and roar inside the hall, the reek of tobacco, stale beer and staler clothes. And Rawbeck lounging against the gilded column, with his handsome coffin-plate of a face that I was to come to know so well gazing dreamily at the lithe, red figure on the stage. She was redeemed from the dark backdrop by the white dazzle of the lime. Rawbeck must have noticed my gaping stare, for the cold, good-humoured eyes were turned to mine.

‘“Like a snake, hey, sir?” he’d said in his lah-de-dah drawl.“Your two hands might span the hips . . .” I was young enough to blush, then, and I glared back, stung by his invasion of my very thoughts, and he laughed, evidently pleased at having read them. Then, after Carrie’s troubling form had left the stage, to thunderous applause, Rawbeck had given me an ironical bow, waving his hand towards the long bar. There was something strangely inviting, and at the same time take-it-or-leave-it, in his gesture, which countered my first instinct to turn my back on him and leave – if only I had obeyed my instinct! – and I joined him rather uneasily at the bar.

‘“A sherry cobbler, sir!” he said, with a tinkling, youthful laugh. “Cools the blood, don’t yer know . . .”

‘Rawbeck talked well, with a sort of raffish erudition mixed with coarseness of the lowest sort, beginning with Carrie in particular and proceeding to Beauty in general – the only thing that redeemed life from the slime, he avowed. He then touched on his inspiration, France, for which he had a passion. When I mentioned tentatively that I had briefly studied art in Paris, our affinity, Rawbeck declared, was sealed, and I earned my first invitation to his high studio in the dim cavern of a street on Camden Hill. I recall the high night sky in jewel-case velvet, all roaring with stars, and – a typical trick from the box of the Master Illusionist – her there, all lithe and dressed again in red.She was Rawbeck’s model, and owed much of her reputation on the halls in no small part to his brilliant posters of her. She eyed me with a frankness that made me blush again to the roots of my hair, and the artist’s teasing laughter rang out again.

‘“I’ll wager you’d like those legs round your neck, hey, sir?”

‘Carrie hooted with vulgar laughter, but as drink was plied – there were kindred spirits at the gathering – and my host became more outrageous, I found, little by little, that I could listen without blushing. And so, at twenty-four, my slavery began – he cheering me on – and my consequent descent into hell.’

Here there was a gap in the narrative, a wad of pages having been torn out of the notebook at some time. When my grandfather’s handwriting took up again after the gap, it was more broken in style, produced, as it seemed, in fits and starts, the downward strokes fairly cutting into the brittle paper. The fresh text began with a title.

‘The Horror . . .’ I read out again from the notebook, and Leah put down the Bible she’d been examining and gave me her full attention, her dark, almond eyes sombre. ‘The Anniversary, and Convocation in Great College Street – with the drinking of the Lapland Mushroom potion – Lord! How can I have been so weak! And all for her! The regale laid on this time in honour of that vile, lisping queen, Toland, for the sake of Rawbeck’s credit with him. With P. F.’s dirge on the flute solemnly mocking me in the background, then the Invocation – blasphemous farce! – and Toland’s blubber lips at my ear – more a kiss than a whispe

r. He lisps that I am to be Seer tonight.

‘I drink the potion – it is gall unspeakable! I retch and retch, amid the circle of dark heads round the glowing brazier, with Toland’s silly voice bleating all the while. The purgatory of pain, then, after an aeon of time, a great ease and concord of the senses.I breathe colours and taste sounds, smell lightness or heaviness, smoothness or roughness, as if I were caressing them with the linings of my nostrils. I expand into vastness, then into a dot of infinite smallness, and the whole universe is filled with my laughter. And the colours! Glowing and coalescing, beyond the range of the prism – colours to which I cannot put names – then confluence into the “white radiance of eternity,” and I am White itself. Boundless joy, beyond thought, beyond the shabby husk of the ego – I have slipped the chains of the tedious jailer behind the eyes. Then a moment of terror: what if I should expand to fill the entire universe? Endless diffusion? But then I laugh again: I am the universe!

‘Now I sense myself leaving Convocation, at first in a disembodied swirl until I become conscious of the silver head of my stick in my palm, which is as sensitive as a second palate. Indeed, I taste the silver – nutmeg and lemon – through that very palm.

Now the shock of the sooty London night air – I am reminded that I have lungs, after all, raw bellows sifting the onion of the oxygen from the soot. Then the hardness of the pavement under my unsteady legs, and the cab-bell jingling like some temple cymbal. I glide somehow into the cab and sink, intoxicated, into the leather upholstery. The cab lurches off down the hill, and I know no more.

‘The Awakening. It is calm and cold, and – Lord! – I am naked! Pitch darkness all around me, then, as my eyes become accustomed to the obscurity, some crack lets in a grey, dimity light. I am no longer a lordly stalker of eternity, drunk on the Mushroom, but a shivering, naked worm. I slip my legs over the side of the bed and stand upright, and, in my doing so, a bombshell of pain explodes inside my head, and I groan out loud.But I am now shivering uncontrollably, and I stoop and grope on the floor for the reassurance of my clothes and boots, find them and somehow pull them on. My mouth is dry as a furnace, and the scimitar that is cleaving my head gives way to a steady throb, like the engine of a steamer. A wave of nausea sweeps over me, and, providentially, the toe of my boot rings against the rim of a chamber pot under the valance. I draw it out quickly, and, stooping again, relieve my stomach.

‘Almost myself once more, I cast my gaze round the shadows of the stale-smelling room, with its few looming blocks of furniture. There is a chink of drawn curtain, and a tenuous ray of yellow gaslight coming in, no doubt from a street lamp outside.I pick up my stick and hat from the bed and make for the curtain, only to stumble against a heavy object on the floor. I lose my balance, and fall down beside the object. I raise myself to my knees and grope along the thing – soft, clothed – a body! My questing hands reach a watch-chain, then, higher up, I gasp as I pull my hands away from a wet obscenity. I climb to my feet, then rush over to the curtains, which I tear apart. The light from the lamp outside streams into the mean room, and I swing round towards the object on the floor, to be mocked – but not for the last time – by Rawbeck’s extinct, ironic smile. The eyes are glazed, and under his chin a red ruin.

‘I dash for the unlocked door, then, fumbling in my pockets for my handkerchief, try to wipe off the blood from my hands as I negotiate the landing and flight of rickety stairs. Then an afterthought stops me in my tracks – my stick! Back, shuddering with loathing, to the room, where I retrieve it, then down the stairs again into the lobby of what is evidently some low public house. There is a double door with frosted windows, and the image of a galleon in full sail, and the stale smells of beer and tobacco. I pause in the grey, dawn light, unable to resist a shuddering glance back up the stairs: it is as if the slaughtered Rawbeck were beckoning me: “A sherry cobbler, sir – nothing like it for cooling the blood . . .”

‘Am I going mad? As I glance up the stairs, I notice a stair-head window with an outside gas lamp illuminating the alternating ruby-and-blue stain along the edges of the glass. The design beguiles me, somehow, then I look down at my hands – in spite of my frantic efforts with my handkerchief, the fingernails are still clotted red, like the talons of a ravening beast.Cain’s mark . . . Lord! Can I have done this thing? I cannot remember – farewell, peace of mind.

‘At last, I turn on my heels and face the street doorway. I grasp for the door bolts, and find – thank God! – the handle of a spring lock. A turn and a click, and I am outside. I pull the brim of my wideawake over my face as I shut the door gently behind me before hurrying off into the cold, greasy streets. I am in some mean quarter of London, one entirely unfamiliar to me.All is silent and deserted, and, my brain beating, I shuffle along for what seems ages. I have a vague sense of water nearby – the Thames? A canal? I rush ahead, thinking only of escape, then a shabby thoroughfare comes into view, with closed shops, and, yes, a stationary hansom ahead.

‘I approach the cab, and tap the dozing driver’s seat with my stick. I give him the name of the nearest railway station to my diggings, and climb in. The cabbie yawns, and without a word, drives off at an easy canter. Once ensconced in the protective darkness, and lulled by the gentle rhythm of the cab-bell, I feel my overstretched nerves slacken, and I slip into slumber before I am woken up by the cabbie’s voice. I climb out, pay him and dismiss him, then make for my rooms, letting myself in with the latch-key. I tiptoe up the carpeted stairs to my quarters and immediately begin to stuff some clothes into a carpet-bag. I go to the dressing table, and clear my things from it, but my razor is not there . . .

‘I freeze, as, with my mind’s eye, I find myself standing again at the foot of the stairs in the house of horror, and, inconsequentially, the window on the stairhead that adjoins the fatal room flashes before me. The throbbing ruby of the window’s stained glass edging seems to reflect the crimson of the throat of what lies inside the room. I shudder again, and return to my senses – the missing razor . . . And then there is relief when I reflect that, though the razor is an heirloom, the initials on the handle are not mine, and so it cannot be traced back to me.Already I am thinking like a fugitive scoundrel! Should I then go to the police? But my people – no, it is unthinkable. And what of my dearest Cecily? She knows nothing of what my life has been of late: am I to repay her steadfastness with this? And if she should find out about Carrie? No, it is not to be thought of.I must go abroad, efface myself and spare the innocent, but how can I ever forgive myself?’

There the writing in the notebook trailed off into a flurry of biblical chapter and verse titles, then a spate of disjointed entries.

‘Rivers,’ I went on reading from the notebook. ‘Home in the East – Soundings A – Reuben’s Court – Smoking Altars . . .’

‘More visions?’ Leah’s deep voice, with its ghost of Leeds, chipped in. ‘Looks like young Sebastian’s been at the magic mushrooms again!’

‘Ah!’ I said. ‘Some more joined-up text. Let’s see . . .’

I carried on reading out my grandfather’s confessions.

‘The studio in Montmartre – I know the madness of jealousy again: she is a very devil! I return from the Salon and find the Vickybird with her – lying on our bed. Lounging, slack-jawed, Cockney impudence – he is after money again, and I don’t doubt, the other thing . . . And Cecily’s gift almost gone – it was to have been my redemption – my escape! I am not fit to kiss the hem of her gown!

‘The Vickybird lounges off, laughing at my futile railing, then Carrie takes up her billingsgate again, and the mockery of her dance when I first saw her in Gatti’s. Her abuse turns to tipsy wheedling – her breath stinks of drink, and her blouse is stale, but I cannot, cannot, resist . . .’

Here another page of the notebook was torn out, so we’d never know how my grandfather coped with Carrie’s raunchy allure on that occasion. I went straight on to the next page, with all of Leah’s attention now from the window seat.

; ‘She is in drink again – I blot out the horrid words – and for the first time I see how ugly she can be – a blowsy slut. Now I could smash down the absurd, bobbing, ginger mop, and the white face, with its squirming, loose lips. Our eyes meet, and, suddenly, hers become calm and sly: she has seen my resolve. It is done between us – over. I know I desire her no longer, and I am free. Her voice is even and indifferent now, and I freeze with horror as she talks of Rawbeck, confirming my worst fears. The Vickybird and the drawings, especially LXXXIII, must be found at all costs, unless – God forbid! – Carbonero already has them, and they are on sale in his atelier. Then, her parting shot – her “condition”, as she puts it, and am I man enough to assume my responsibilities? But I had anticipated that: the arrangements are already in place.’

At this point the narrative made one of its abrupt shifts of topic, resuming on the next page under a new heading.

‘Gare du Nord,’ I read out from the scruffy little book. ‘My Angel, my Goddess is there. We embrace, and I am embedded in the very scent of home. I am unmanned for a moment, and she comforts me, stopping my blurted confessions with her dearest finger. Then the boat-train hisses and clanks its arrival, and Cecily draws her veil down firmly as we enter the compartment, with the prospect of England and salvation in front of us.’

There were only blank pages after that, and I put down the book on the cane sofa.

‘Well,’ Leah said with a low whistle, ‘is that a story, or is it a story! This is your next book, Seb – you know that, don’t you?’

‘It’s been dropped in my lap like a gift,’ I said with a sort of wonder. ‘There’s always been a virtual rule of silence in the family about my grandfather’s early life, before he became a clergyman, and now this! I’d no idea he’d studied art in Paris, for one thing, or that my grandmother had pulled him out of such a scrape . . .’

‘She’d have been his Cecily, his Angel and so on, who “took him away from all that” at the Paris station to a new life in England?’

The Ruffian on the Stair

The Ruffian on the Stair